Cliodynamics: a science for predicting the future

"Physics envy" is one name for it. It's the epithet that people in the physical sciences sometimes mockingly lob at research in other fields that, they think, tries to hide its lack of conceptual or empirical rigor behind gratuitous equations and vague metrics. Psychology, sociology, even areas of biology and economics get tagged with it. But history? Recently, there hasn't been much reason to accuse historians of physics envy.

"Physics envy" is one name for it. It's the epithet that people in the physical sciences sometimes mockingly lob at research in other fields that, they think, tries to hide its lack of conceptual or empirical rigor behind gratuitous equations and vague metrics. Psychology, sociology, even areas of biology and economics get tagged with it. But history? Recently, there hasn't been much reason to accuse historians of physics envy.

Yet Peter Turchin, a mathematical ecologist turned history analyst at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, is now stirring up exactly those kinds of criticisms -- even from other historians. He is a founder and leading proponent for a young field of quantitative historical study called cliodynamics (after Clio, the Greek muse of history). His new science aims to identify not just trends or patterns in human affairs but actual laws that may govern the stability of societies over time.

That many historians regard the search for such laws to be hopeless doesn't seem to discourage Turchin. He and his colleagues already see evidence for principles that explain past patterns and that just might also predict future trends.

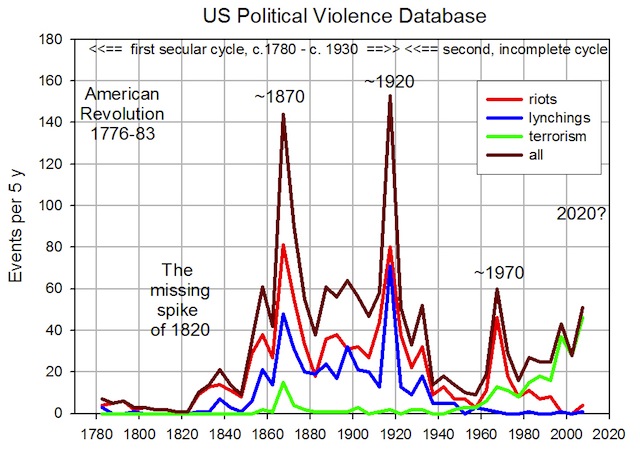

In an article appearing in the July issue of the Journal of Peace Research, "Dynamics of political instability in the United States, 1780-2010" [pdf] Turchin argues that cyclic interactions of demographics, economics, and violence explain waves of political unrest that break over the country at 50 year intervals. One implication of his work, if correct, is that the U.S. could be heading for another crest in instability around 2020.

Should we take this seriously? Can we afford not to?

200 falls of the Roman Empire

Turchin began developing cliodynamics in the late 1990s partly out of frustration at what he saw as the unwillingness of historians to do more than theorize about the causes of historical events: they didn't try to rigorously test their ideas and discard the inadequate ones. As he wrote in a 2008 essay for Nature, "Arise 'cliodynamics'":

What caused the collapse of the Roman Empire? More than 200 explanations have been proposed, but there is no consensus about which explanations are plausible and which should be rejected. This situation is as risible as if, in physics, phlogiston theory and thermodynamics coexisted on equal terms.

This state of affairs is holding us back. ... [W]e need a historical social science, because processes that operate over long timescales can affect the health of societies. It is time for history to become an analytical, and even a predictive, science.

What convinces him that such a predictive science is possible is that when he and his collaborators Sergey Nefedov and Andrey Korotayev have looked back at various agrarian, pre-industrial societies throughout history, they have found "empirical regularities" in the indicators of social instability. The so-called secular cycles responsible for those fluctuations, Turchin and his colleagues say, embody the action of some principles governing the dynamics of how all societies work.

According to a "structural-demographic theory" that they offer as an explanation, the affluence at the beginning of a secular cycle starts to fold as population growth outstrips productivity. The expanded population also creates more competition for political power, while the rising costs of the state become more burdensome. Eventually, the combination of problems triggers a breakdown in central authority, and the unrest lowers the population enough to reset the cycle.

In his new paper, Turchin sees signs of this same principle at work in U.S. records over the past 230 years for reported episodes of violence related to politics, labor relations, racism, vigilantism, and terrorism. He found that although the causes varied over time, the social unrest embodied by that violence peaked every five decades, in 1870 (during and after the Civil War), 1920 (just after World War I), and 1970 (during the Vietnam War and after the tumultuous decade of civil rights activism). It presumably would peak again in 2020. Turchin can't say precisely where that violence might occur, or how bad it would be, or who would be responsible for it, but his work seems to suggest that a confluence of circumstances will push somebody (or more accurately, many somebodies) to it.

The long history of scientific history

And Turchin is certainly far from the first to think about using mathematical methods to make history more predictive. Science fiction author Isaac Asimov famously dreamed up the science of psychohistory to propel the plot of his Foundation novels. Like cliodynamics, Asimov's fictional psychohistory relied on statistical methods and sociological, psychological, and economic knowledge to predict social trends. In Asimov's books, psychohistorians used their skills to predict and guide the fall of one galactic empire and the rise of a new one over thousands of years.

Here on Earth more than 2,100 years ago, the ancient Greek historian Polybius developed the concept of anacyclosis, which held that over time, societies evolved through a predictable cycle of governments -- primitive monarchy, enlightened monarchy, tyranny, aristocracy, oligarchy, democracy, mob rule, and then back to primitive monarchy again. The accumulating failures and abuses of one form of government would propel societies to embrace the next as a solution until it, too, collapsed from its failures.

The German historian Oswald Spengler proposed a highly influential, widely disputed theory about the rise and collapse of civilizations in his book The Decline of the West (1918), which argued that World War I and German's post-war turmoil were symptomatic of a grand, sweeping historical rot bringing down European culture.

In the early 1970s, at the behest of the Club of Rome, Jay Forrester of MIT's Sloan School of Management adapted the complex corporate modeling methodology called systems dynamics to anticipate how the global socioeconomic system would respond to population pressures and environmental threats. He described his results in his book World Dynamics.

Today there is the technological futurism of Ray Kurzweil and others. His methodology takes a page from Moore's Law and posits a steadily accelerating improvement in technological capacities. Not too surprisingly, exponential growth being what it is, technology thus becomes the single most important force in all of human affairs, and in Kurzweil's scarcely restrained imagination, it sweeps all social issues and mortal concerns aside. Within decades, it brings all of humanity to a technological Singularity, when new superior intelligences born of computing and nanotech will take control of progress and everyone can live forever with one's resurrected loved ones in a universe of infinite options. (As theories of history go, this one puts Manifest Destiny to shame.)

And those are just a few of the thinkers who have tried to develop empirical theories of history and models for future trends.

Prediction is hard, especially about the future

The problem, however, as journalist Laura Spinney explains in her recent well-reported article about cliodynamics for Nature, is that most historians maintain that the unifying "laws of history" Turchin seeks don't really exist: people are too unpredictable, historical parallels are at best only approximations, and so on.

To these skeptics, the empirical regularities that the cliodynamicists see aren't trustworthy because historical records are also too inconsistent to provide reliable data. It isn't enough to look for recurring patterns that might represent transcendent historical principles. One also has to try to disprove the existence of those patterns by making sure they only recur where theory says they should, and to validate alternative explanations.

The regular patterns of political instability that Turchin finds might indeed be the result of recurring structural and demographic tendencies. Or perhaps they result from the periodic confluence of circumstances. Or maybe the historical record of the U.S. is simply not yet long enough or complete enough to draw such conclusions with confidence. Turchin has tried to address all these challenges in his analysis, but it may take many such lines of evidence to persuade most historians.

Another problem with the predictive aspect of cliodynamics is that, so far at least, the predictions are rather blasé. Turchin might be right that the U.S. is entering a period of increased unrest and social instability. Yet plenty of people come to exactly that same conclusion, with no fewer particulars than Turchin offers, simply by turning on CNN. It's possible for a predictive science to be valid yet lack significant value. If that were the best that cliodynamics had to offer, what good would it be?

Testing the past

Whether or not one has faith in Turchin's cliodynamics, however, his endeavor is worth contemplating. If nothing else, it's an opportunity to reflect on what we think history and science really are.

For example, do you subscribe to the "great man" theory of history, which argues that certain highly influential individuals can uniquely alter the course of global events? Or do you have more confidence in the idea that historically important individuals are really just the faces of larger operating trends, and that individual actors ultimately matter very little?

To claim legitimacy, must every science, including social ones, aspire to have the mathematical foundation and emphasis on quantification that physics has? Evolutionary biology is a well developed science but that doesn't mean it can explain precisely why forms of life evolved as they did, or predict precisely how they may respond to new environmental challenges. -- But then again, wouldn’t most biologists consider it a plus if they could make such predictions?

All this talk of predictions may put too much emphasis on using cliodynamics to anticipate what is to come. As Turchin wrote in 2008:

[S]cientific prediction is a broader concept than merely forecasting the future. It can be used to test theories. For example, two rival theories may make different predictions about the behaviour of some variable, such as birth rate, under certain social conditions. We then ask historians to explore the archives, or archaeologists to dig up data, and determine which theory's predictions best fit the data. Such retrospective prediction, or 'retrodiction', is the life-blood of historical disciplines such as astrophysics and evolutionary biology.

He also notes:

Cliodynamic theories will not be able to predict the future, even after they have passed empirical tests. Accurate forecasts are often impossible because of phenomena such as mathematical chaos, free will and the self-defeating prophecy. But we should be able to use theories in other, perhaps more helpful, ways: to calculate the consequences of our social choices, to encourage the development of social systems in desired directions, and to avoid unintended consequences. ... To truly learn from history, we must transform it into a science.

•

Top image: (Credit: Mark Skipper/Bitterjug, via Flickr)

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com