Where's the (grass-fed) beef? Expanding 'locavore' products

The butchers holding long knives were clad completely in white, their breath misting in the near-freezing air as they sliced cuts of beef from carcass after carcass. The sterile metal tables were surrounded by cow and pig bodies hung from hooks, and the whir of fans intermingled with the echo of synth-pop blaring over the radio.

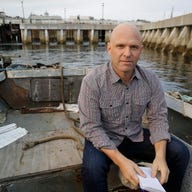

David Evans, a barrel-chested, fifth-generation California rancher, walked by slowly and inspected the work. Many of these cattle were raised in the briny air and fertile grasses that grow on the seaside pastures of his ranch on California's North Coast.

Each butcher was hired for his attention to detail and knowledge of the beasts' physiology to ensure that no part is wasted -- innards and all.

"These aren't butchers," Evans said, "they're artists."

This tableau was not unfolding in some agricultural heartland but just a few blocks from the glimmering new offices of Twitter in the heart of San Francisco. Evans' new Marin Sun Farms custom, hand-cut meat- processing facility lies in the midst of technological innovation. While Marin’s employees wear hardhats and gloves instead of skinny jeans, there is a key similarity between this old-school business and its modern neighbors: Evans is trying to force a similar "disruptive" wave of change over the traditional meat business by giving small producers who focus on humane handling and sustainable agriculture access to a larger-scale processing infrastructure and a bigger market share.

All of the cattle being cut were from ranches within a 200-mile radius -- farms that until now had few options for meat processors that can deliver their pasture-raised meats to a burgeoning consumer market demand.

"One of the biggest issues facing the grass-fed business is finding small processors," said Marilyn Noble, communications director for the American Grassfed Association in Denver, Colo. "The big processors have to shut down and clean everything before putting the grass-fed meats through. They're processing more than 400 animals an hour, and a grass-fed rancher might have 100 total. It doesn't make much economic sense.

"The small processors all went away when the country moved to this kind of industrial agriculture decades ago."

A gamble

There is huge risk in Evans' endeavor since much of the pasture-raised, grass-fed meat business is seasonal, meaning small processors struggle keeping year-around work.

And while there's a lot of talk from celebrity chefs about eating local and buying responsibly-produced food, Evans is putting his money where his mouth is: about $3 million in startup costs alone. He has become an evangelist for the power of small-business collectives to change the nation's meat system.

Evans' gamble, started about two months ago, was to invest heavily in an early incarnation of that infrastructure -- creating a large-scale, full-carcass, hand-cut meat plant to meet a demand that Marin Sun Farms believes is there.

"The commitment to whole carcass is (about) enforcing integrity within the meat system and in the economic system, of bringing to justice our cumulative wants, forcing us to digest the whole beast," Evans said. "Our individual eating choices affect the environment far from our front porches."

To be truly successful, he will need a larger portion of the public to embrace less-popular cuts of meat -- and perhaps even offal (the guts) -- so the whole animal can become more profitable. Traditional meat purveyors sell only the most popular cuts of meat, New York strips and ribeyes, for example, and often rely on a global marketplace to meet demand. This leaves less-popular portions of cows, pigs and other animals not economically valuable, making more expensive locally-grown cows as valuable as the sum of their most popular parts.

Industry observers have already seen a marked shift in consumer knowledge of rare cuts.

"A lot of consumers are seeing cuts like short ribs and oxtails -- 10 years ago no one knew what they were, and now it's not unusual to see them on restaurant menus," Noble said. Still, while offal has gained some popularity among fine diners, it's proven a tougher sell in the mainstream.

Evans hopes success will provide a blueprint for others and begin a national system of regional full-carcass, custom-cut meat processing plants that will help more people eat within their "food shed," the industry term for foods grown or raised within a few hundred miles of where the end-line consumers live.

"Since the concept of sustainability applied to ecosystems, food systems, health and agriculture have only recently become mainstream, we are working toward that goal," Evans said. "By building out livestock processing infrastructure, like the (San Francisco facility), we can now support the growing number of farms in (California) that are more and more focusing on a sustainable future food system."

A changing meat marketplace

Like any good gambler, Marin Sun Farms and its partners see market data and consumer preference trending their way. And people with a strong preference are willing to pay a premium for meat they know is sourced humanely and locally, which cuts the amount of energy it takes to deliver it to their plates.

"Grass-fed is definitely a niche market, but it is seeing tremendous growth with the increase in interest in local, natural and organic meats," said Mary Reardon, a spokeswoman with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service.

Currently, meats from ranches similar to Marin Sun Farms make up about 3 percent of the U.S. beef market, but the USDA estimates a yearly growth rate of 20 percent.

"Continued growth at current rates could double market shares for these products every five years, although it is unlikely that such growth will continue beyond a certain threshold," the economic research service said in a report released in April.

To understand why a rapidly expanding market exists for humanely-raised, grass-fed beef, it's important to understand why conventional meat is raised the way it is.

Cattle production in the United States was forage-based for decades until the use of land for crops -- think corn, wheat -- ended up competing with the land used by cattle to graze. Farmers could make more money per acre, generally, growing things rather than grazing cattle.

At about the same time, ranchers started feeding cows, which were increasingly less able to roam freely and graze in open fields, the grains being grown. This had two major effects: it shortened the amount of time needed to produce a cow for slaughter and made meat more tender, with swishes of fat marbling throughout.

Today, 80 percent of U.S. cattle are "finished" with grain and corn-based products -- meaning after they reach a certain age they're brought to feedlots to be fattened up before slaughter. In the lots, the cows are fed sometimes with foods laced with antibiotics and hormones, and they can grow from 600 to 900 pounds up to 1,200 to 1,500 pound in five to six months, according to the USDA Economic Research Service.

As books like Michael Pollan's "Ominvore's Dilemma," published in 2006, and others exposed more of the public to the modern meat industry, the business for alternatives skyrocketed.

But while there were producers like Marin Sun Farms ready to fill the need, the industry wasn't ready. USDA-approved slaughterhouses and processing facilities were created for large-scale meat companies.

"Large plants with scale economies, even if conveniently located, are essentially unavailable to local meat producers due to mismatches in scale, services and business models," according USDA's report.

So a need existed for a larger scale processing facility -- the new one is 18,000 square feet and currently employs 15 full-time butchers with room to grow -- that could do the custom work needed by ranchers committed to non-traditional meats. But Evans and his ilk needed a large, wealthy client base to act as early adopters and help propel them to the mainstream.

Luckily, these local ranchers shared a proximity to Silicon Valley.

Silicon Valley's influence

Chef Jean Claude Balek is serious about meat, but the "right" meat. He wears his heart on his sleeve and his politics on his knuckles, where he has the word "locavore" tattooed.

Google's former executive chef, Balek now works in the same capacity at Palo Alto, Calif.-based Palantir Technologies, a software company started by PayPal alums and some Stanford computer scientists.

His goal is to source all foods served at Palentir from within 200 miles.

"It's almost as important as the animals being treated well," Balek said about sourcing his food locally. Even though he pays more to buy it, he knows exactly where it came from. One of the benefits of sourcing food close by is you can visit the source.

Balek spent time working with Evans on the ranch and seeing firsthand how the animals were treated and raised, digging ditches and spending time with the creatures he would one day be serving.

"Growing a relationship with your local ranchers helps guarantee your money stays in the local foodshed," Balek said. "It's almost as important to me as the animals being treated well."

Right now, Balek buys two full cow carcasses every two months, and full pigs, from Marin Sun Farms. Other clients helping keep Marin Sun Farms' new meat plant afloat include chefs at Apple, Oracle and Stanford University. Celebrity chef and San Francisco restaurateur Tyler Florence is also a client.

Next, Evans is looking to the expanding market in Los Angeles.

"I've found that chefs in L.A. also value relationships with local farmers and ranchers -- when possible. Local, grass-fed and pasture-raised meat can be very tough to find year-round," Evans said. "As a result, these chefs, even those who value local, have to go outside California to find livestock raised this way."

Growth limits

Just how far this "alternative" meat industry can go is limited in part by one of its biggest selling points: environmental impact. As more land is needed to "finish" cattle in the field as opposed to feedlots, vast land areas currently populated by plants -- which remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere -- could be replaced with methane-producing ruminants.

"Some studies suggest that shifts in land-use allocations may increase both GHG emissions by range livestock and incentives to bring sensitive marginal land into production," the USDA said.

Chefs like Balek who have embraced the local and believe in its overall good say there is a balance, but that the relationships between people and their environment, food producers and each other are worth pursuing.

"With more demand for this kind of meat, the issue will be land in the end," he said. "But the more people who support this ... it will do wonders for the future."

Photos: David Cuetter for SmartPlanet. For more exclusive photographs from inside the Marin Sun Farms facility, see our photo essay here.

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com