The child of a middle-class family -- his father was an engineer, his mother an administrator -- Ma did not venture outside of the city much. He read books and poems that described China’s rivers, mountains and natural landscapes and painted mental pictures of his country’s natural wonders, never once realizing that much of the pristine environment of which he read was being torn apart.

"At that time, every five to 10 minutes there was only one car coming from either side of the road. Now, Beijing’s roads are just so crowded, even in the evening. And the bugs are no longer there, those beautiful things have gone," he said. The canal's water where he fished and swam as a kid is now too polluted to sustain life.

Since Mao Zedong's call for "Man to Conquer Nature" in the mid-20th Century, environmental concerns have taken a backseat to economic growth in China. This has made the nation an economic world power, but has also created some of the world's worst air and water pollution, deforestation and dangers to public health. For decades, the Chinese people had little access to pollution data from their government, and multinational companies using Chinese factories that were egregious polluters went largely scot-free. To worsen matters, the Chinese justice system lacks the independent judiciary needed so citizens can successfully sue for damages when their local river or air is contaminated.

Today, the boy who once chased bugs under Beijing’s streetlamps is innovating Chinese environmentalism by giving people and businesses what they’ve never had before -- easy access to pollution records. The results have been staggering: investigative reports by Ma’s Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE) have ignited public pressure on some of the world’s biggest companies like Nike, General Electric, Apple and Walmart to take responsibility for their supply chains.

Ma’s IPE has developed pollution databases and online maps that give citizens and companies doing business in China, where production is cheap, the evidence they need to build cases against polluters in the media, since Chinese courts offer little hope of redress.

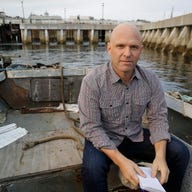

The soft-spoken man with the quiet intensity may seem a reluctant warrior, but those who know him say his work to expose labor and environmental crimes at Chinese factories is fierce and tireless.

Robert Percival, a U.S.-China environmental law expert who teaches at University of Maryland’s Francis King Carey School of Law, said in 2009 that a quiet man approached him after a talk he had given in China. It was Ma Jun, and he was holding a copy of Percival's environmental law casebook.

"He asked me to autograph it for him because he said that it had changed his life," Percival said. "I then had lunch with him and was very impressed with his modest, low-key style for someone who I had been dying to meet given his tremendous accomplishments in China."

Muckraking

In his 20s, Ma became an investigative environmental journalist for the South China Morning Post, one of the country’s few muckrakers. This gave him his first chance to travel to the rural areas he'd read about and committed to memory.

"Talking with some of the people in these towns and cities, which used to be called 'oriental paradise on earth,' in reality the water now is no longer usable."

Ma’s work as a journalist gave him a foundation to understand the power of information and how the media, if given access to data, can help drive real change.

In his book “China’s Water Crisis,” Ma sought to use this power to enrage the public. While the book is considered a hallmark of Chinese investigative reporting, he realized much more needed to be done to spur the kind of change he envisioned.

"Our issues are so big, these challenges cannot be solved without extensive public participation," he said in a telephone interview from his home in Beijing. "The Chinese public have to build up their awareness and start putting pressure on the business."

After writing his book, Ma realized that without persistent public awareness and participation in the environmental health of their country, change would be impossible. Like the United States and Europe, China has passed significant environmental reforms since the 1970s. But enforcement of those laws has been piecemeal at best, and public access to pollution data about its own air and water was closely guarded by the government.

So, in 2006 Ma stared IPE. The group posted a water pollution map online based on government records. It followed with two databases of air and water pollution violation records spanning years. The initial response was tepid by the public, which had not previously seen such transparency.

The government passed new transparency regulations in 2008, granting access to pollution data for the first time. Still, China's regulatory system is set up into regional fiefdoms, so enforcement was inconsistent -- or nonexistent in some provinces. But IPE was there to start gathering and organizing the data, giving real teeth to the new regulations by pressuring agencies to release records and making them easily accessible.

“We can use transparency as a tool in environmental (enforcement)," Ma said. "America started doing that in late 1980s with pretty amazing results. Now China has leapfrogged into this information age, and our Web users have grown very significantly, which knocked down the cost of doing the environmental transparency.”

The databases gave journalists and environmental activists in China easy, quick access to government pollution records.

“I feel that there's a historic opportunity to do that in China. But the potential has not been tapped, because there's a lack of transparency here. But it's got to be a sustained effort.”

Multinational offenders

Still, Ma said, vast public participation was slow going: the information was there, but few were using it. While environmentalism had taken root decades before in China, the sea change Ma wanted and that he hoped to spark by using the Internet was not immediate.

While doing an environmental consulting job for Western companies that used Chinese factories, Ma had an epiphany.

“We needed the Chinese public and Western consumers who cared about this to build awareness and to start putting pressure on the business.”

Ma realized environmentally-minded Western consumers would have a bigger effect on U.S. companies than the Chinese.

So IPE wrote a scathing report that linked 29 multinational electronics firms with some of China’s most egregious polluters. The report was aimed at Western media, and it found immediate takers. The group's reports have been covered closely by the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and other of the biggest media in the United States.

Of the 29 companies targeted in IPE's first report, only one did not respond: Apple.

"Our interaction with Apple in the beginning was not very smooth," Ma said, "but then all these stakeholders, including Apple's own clients and investors, started reading the questions posed in the report, and consumers started writing to them."

Elizabeth Economy, the head of Asia studies for the Council on Foreign Relations, said his approach was crucial in getting action. “The key to Ma Jun's success is two-fold: he always offers a carrot, which is the opportunity to work with him to develop best practices, while at the same time holding out a stick, which is the threat of very public exposure,” Economy said.

“Given his beginnings as a journalist, he fully understands the power of the media and how to use it for shaming purposes.”

Walmart was one of the first major companies to realize the benefits of working with Ma Jun, and in 2008 it began using IPE’s database to identify factories in its supply chain that were problematic.

For a company that sources from tens of thousands of factories, most of which they have never seen, the information provided by IPE’s databases was a powerful tool the retailing titan could use to help clean up its supply chain.

Other large businesses began taking notes.

Biting the Apple

While large IT companies like Siemans, Alcatel and Nokia began working with IPE’s databases to make more informed choices about Chinese business partners, the world’s largest company, Apple, wasn’t quick to hop on board.

In January 2011, IPE and other environmental organizations took square aim at the tech titan.

In “The Other Side of Apple,” an investigation found more than 27 Chinese suppliers to Apple had environmental problems that violated the company’s own stated standards. In fact, the report called out what appeared to be the company’s seeming ignorance of what was happening at the factories it used.

“In the ‘2011 Supplier Responsibility Report’ published by Apple Inc., where core violations were discovered from the 36 audits, not a single violation was based on environmental pollution,” the report said. “The public has no way of knowing if Apple is even aware of these problems.”

For months after the report was published, Apple ignored the group's calls for a meeting to discuss the findings.

But Ma and his group were relentless in their pursuit of Apple. They provided details of Foxconn workers being hospitalized after cleaning Apple's iPad and iPhone touch screens with dangerous chemicals and highlighted high rates of suicide among the workers to paint a portrait of dire working conditions.

They also documented sometimes outrageous pollution. Using data collected by Ma, a number of significant environmental violations at companies that made parts or assembled Apple's products were exposed.

One factory used by Apple, Dongguan Shengyi, was the subject of constant pollution complaints from its neighbors. The complaints were ignored until IPE unearthed records that exposed the magnitude of the company’s pollution.

"In 2009, this company produced 7831.98 tons of hazardous waste, making it Dongguan City‘s number one company for producing hazardous waste, surpassing the number two and three companies collectively," the report stated.

Apple, which has cultivated the image of a globally-responsible company with a customer hoard of fashionable sophisticates, was not amused. Its stated "supplier responsibility" policy said the company was committed to "dignity and respect" for workers and "environmentally-responsible manufacturing processes."

"His work spearheading the audit of the supply chain of major multinational electronics companies and his ability to persuade Apple to agree to future independent audits have helped win him global acclaim," Percival said.

The public scrutiny, backed by hard evidence and records, worked.

Apple has agreed to third-party audits of its supply chain in China, with the first of these being completed in June for Meiko Electronics Co. Ltd.

With the help of local fishermen, IPE and others had found that Meiko -- which makes some of the tiny, customized internal circuit boards for Apple and other electronics companies -- was dumping waste into a storm water channel, which drained into neighboring Nantaizi Lake.

Water tests showed the lake was seriously polluted with heavy metals, copper and nickel.

"The audit confirmed that the factory had taken major corrective action to fix the issues cited in our Apple report," Ma said.

Apple did not return a call seeking comment about the changes it's made to its global supply chain policy.

Turning point

To date, IPE has exposed more than 90,000 air and water violations by local and multinational companies in China.

Earlier this year, Ma accepted the Goldman Environmental Prize in San Francisco, the Nobel Prize of the environmental world.

“This could be some turning point in our general environmental governance,” Ma said.

“Our current system is made to ensure a very rapid economic growth, but if people can make their voices heard and obstruct that kind of breakneck expansion, then the whole system must be revealed and (there is) a chance for a real transformation in China.”

Photo courtesy Goldman Environmental Prize

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com