The plastic legacy of Great East Japan tsunami debris

The tsunami that followed the Great East Japan Earthquake caused a staggering loss of life, and led to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear meltdown. It also jettisoned millions of tons of debris into the Pacific. It's very difficult to know just how much debris was dragged out, but estimates put it at anywhere from 5 to 20 million tons.

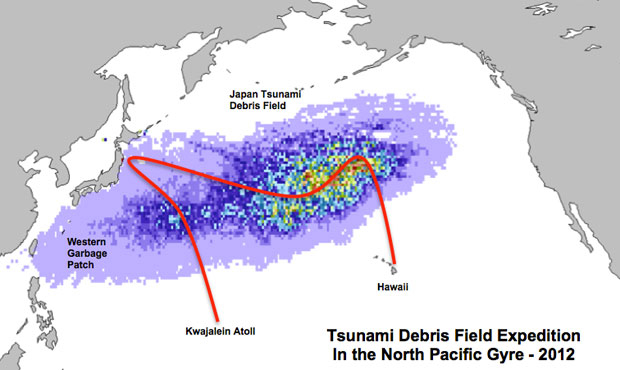

Much of that debris is now likely swirling around the North Pacific Gyre, a vortex formed by prevailing wind-generated ocean currents. This happens to also be the home of what has become colloquially known as the Great Western Garbage Patch. Since this high concentration of plastic pollution was discovered in 1997, we've learned that, unsurprisingly, the same mash-up of plastic garbage has formed in four additional ocean gyres.

But the debris field from the tsunami represents an interesting opportunity for research groups to study the ways plastic impacts our oceans, marine life, and us. One such group, 5 Gyres, will spend three weeks sailing through the North Pacific Gyre off Japan this summer, taking samples of the plastic they find in the water, for analysis. Unlike most of the plastic that is cast into the ocean slowly over time, through human carelessness, the tsunami debris entered en masse and on a known date.

"Based on the estimate [5 to 20 million tons] of debris [that entered the ocean], I would guess somewhere between half to one and a half million tons of what's remaining is plastic or material made buoyant by trapped air," says Marcus Eriksen, 5 Gyres co-founder.

The 2004 tsunami from the Indian Ocean also generated a large debris field, but it was "far away, an equator apart" from the Indian Ocean Gyre, says Eriksen, and so most of it likely washed back ashore. Debris from tsunamis in the 70s and 60s would have contained markedly less plastic, given the surge of plastic use, particularly in packaging, since then.

By studying plastic that entered the North Pacific Gyre after the tsunami, Eriksen and his crew may better understand the rate at which different types of plastics photo-degrade (that is, break down into smaller parts, thanks to UV exposure and wave action).

Large pieces of plastic harm marine animals in obvious ways -- birds often ingest plastic bottle caps thinking they are food, for example. But as the plastic breaks down into smaller and smaller pellets, it is ingested by fish and by what ingests the fish, thereby bioaccumulating. Much is still unknown about the consequences. But in past expeditions to the world's gyres, 5 Gyres found traces of plastic 235 of 237 water samples taken from the ocean's surface.

Another unique aspect of the tsunami debris is that it could be acting as a conveyance for transporting marine species into new regions of the ocean where they're not endemic. "With this amount of debris [from the tsunami], it's possible that few dozen coastal fish species off Japan could make their way to Hawaii," says Ericksen. The fish could swim inside a large plastic crate, for example, as it moves into the gyre and, perhaps, gets spit out further south. If this happens, even just one or two of these invasive species could wreak havoc on the ecosystem.

Image: 5 Gyres/IPRC

More from the Collateral Damage series:

- Q&A: Hitoshi Abe on design lessons from the Great East Japan earthquake

- Listen to Japan's 9.0 earthquake

- In post-Japan quake & tsunami era, Noah offers emergency shelter

- Fukushima's Lesson: 'Alternative' nuclear, not 'no' nuclear

- Asian Super Grid: How Japan's anti-nuclear plan could go nuclear

- A year after Fukushima, how life in Japan has changed

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com