Remember ozone holes? NASA just found a big one

But an international protocol is improving the situation, it says. Is that a model for CO2 emissions?

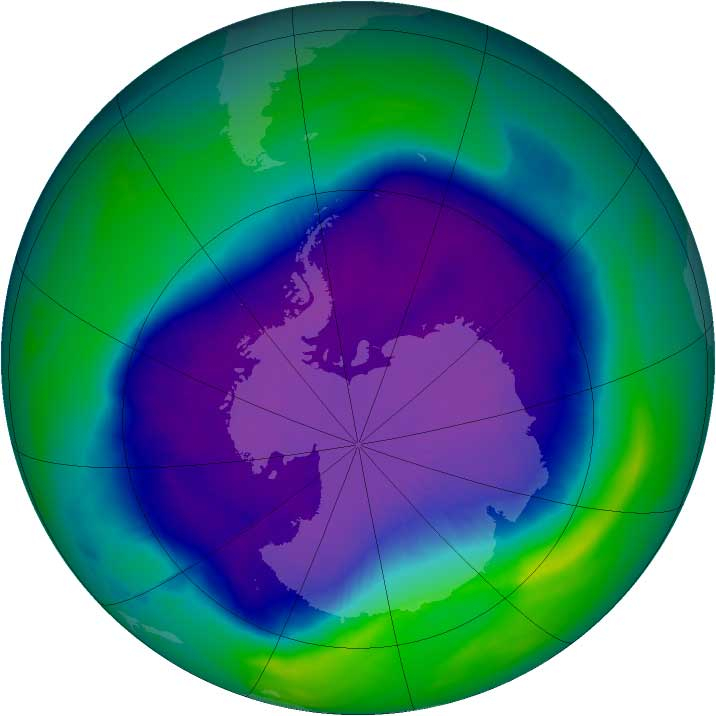

While CO2 emissions grab the energy and environmental headlines, NASA last month spotted the ninth largest ozone hole on record.

You remember ozone holes: Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) from aerosol cans and refrigerators deplete the earth’s protective ozone layer and thus allow more ultraviolet radiation through, elevating the risk of skin cancer, cataracts, and other maladies. It’s especially bad over Antarctica.

Back in 1987 almost  200 nations signed up to the Montreal Protocol, which phases out the use of ozone-damaging chemicals. It’s working. Atmospheric CFCs peaked in 2000, according to NASA.

200 nations signed up to the Montreal Protocol, which phases out the use of ozone-damaging chemicals. It’s working. Atmospheric CFCs peaked in 2000, according to NASA.

And yet NASA spotted one of the most gaping holes on record last month when the Antarctic ozone hole reached its annual southern hemisphere spring peak on Sept. 12.

“It stretched to 10.05 million square miles, the ninth largest ozone hole on record,” NASA reported in a press release. It has been measuring ozone holes for over 30 years.

The space agency wasn’t surprised, because CFCs have a long lifetime.

"Even though it was relatively large, the area of this year's ozone hole was within the range we'd expect given the levels of manmade ozone-depleting chemicals that continue to persist in the atmosphere,” said Paul Newman, chief scientist for atmospheres at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "In 2100, CFCs will still be 20 percent more abundant in the atmosphere than they were in 1950. So while it's not getting any worse, it won't get better fast."

As James Butler, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Global Monitoring Division in Boulder, Colo., noted, "The manmade chemicals known to destroy ozone are slowly declining because of international action, but there are still large amounts of these chemicals doing damage.”

Ozone’s story seems to offer a couple of lessons to the troubled international efforts to cohesively reduce emissions of greenhouse gases like CO2 – an area where the U.N.'s Copenhagen Climate Change Conference infamously fell short nearly two years ago.

One is that a couple hundred countries canagree to measures with teeth.

But another is that such measures take time to yield real results.

For CO2 optimists, the Montreal Protocol on ozone improvement provides hope. For doom-and-gloomers, the Sept. 12 ozone hole might reaffirm that it’s too late to take any effective measures. For those who think global warming is a bunch of malarkey, nothing changes.

Your thoughts?

Images: NASA

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com