MoMA explores 20th-century toy design in fun, smart exhibition

NEW YORK--"Century of the Child: Growing by Design, 1900-2000" is an ambitious museum exhibition that is at once sprawling, fun, and emotionally and intellectually demanding, much like the experience of childhood itself.

On view at the Museum of Modern Art through November 5, it features more than 500 objects, ranging from beautiful clothing to elegant modernist chairs to creepy political propaganda in the form of toys. Organized by Juliet Kinchin, curator, and Aidan O'Connor, curatorial assistant, both in MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design, the show is smart and highly entertaining.

The exhibition opens with charming drama. In the sixth-floor galleries of MoMA viewers are greeted by a humungous, blown-up photographic image of a little boy climbing a wall, taken by Jens Jensen in the 1970s (below). It's placed across from a black-and-white film projection of a child riding a bike-like contraption in the 1920s. Both works present kids engaged in joyful play, with the same happy grin on their faces, despite the 50 years between them.

In the middle of the first gallery of the show is a wonderful sculpture consisting of giant-sized kids furniture: an iconic adjustable Tripp Trapp high chair, wooden table, and child's seat. They were designed by the Tripp Trapp's creator, Peter Opsvik, and scaled so that any full-grown adult who dares to sit on the chairs appears to be the size of a three-year-old toddler. On the day that I visited the exhibition, there were numerous groups of grown-ups posing on the furniture, their friends and family members snapping their pictures, despite the "no photography" signs nearby. The show is that playful, the designs that inviting, that for a moment, even adults want to revert back to childlike impishness.

ADDRESSING CHILDREN'S RIGHTS, SHAPING THEIR FUTURES

The curators were inspired by a manifesto published in 1900 by a Swedish social theorist named Ellen Key. In this publication, Key argued for children's rights, calling for adults to pay better attention to their off-springs' well-being. The span of the exhibition--the entire 20th century--reflects a period of extraordinary reform in not only education, healthcare, and labor laws for kids, but also for women. As more women entered the field of design during the 20th century, they also designed products for their children.

"The connection between design and developments in children's and women's rights is a core theme of our exhibition. A priority in the planning of the exhibition was to feature the contributions of women -- as designers, educators, and reformers," Aidan O'Connor, co-curator, told SmartPlanet in an e-mail. On view, for instance, are educational materials created by the late Maria Montessori, the Italian doctor and educator whose teaching methods are widely in use today.

NOSTALGIA AND DEJA VU

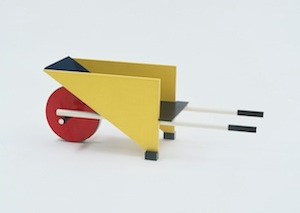

There are so many striking pieces on view, likely to have various generations of viewers feeling nostalgic. For younger parents, a sense of deja vu is likely to prevail. Design fans will love looking at a cool Modernist doll house and elfin chairs made for tots by design legends Marcel Breuer, Charles Eames, and Alvar Aalto. A 1930s Skippy Racer Scooter (shown at top) and wooden building blocks from the 1940s look eerily contemporary--or at least fit the current fashion of retro toys. Some objects are truly works of art, such as an angular wheelbarrow designed by Gerrit Rietveld--a prominent member the Dutch De Stijl art movement--in the 1950s.

The galleries are brilliantly color-coded, in terms of the wall paint chosen by the curators, to help illustrate the evolution of design for children. The first section, which covers the era between 1900 and World War I, is presented among walls painted an elegant dark blue, which matches the sophisticated aesthetic of the Art Nouveau era and the Arts and Crafts movement. Later, we see the more familiar bright primary colors and gentle pastel colors that have come to signify a happy and safe childhood.

After the section on Art Nouveau and the Arts and Crafts movements is a set of galleries devoted to "Avant Garde Playtime," covering well known trends in art and design that surfaced in the 1920s and 1930s. The curators draw comparisons between the vivid imaginations of the European avant grade and kids' wild and glorious creativity. The next section of the show looks at the idealism behind the design for kids that surfaced between the two World Wars--and how both safety and the transformation of society were top of mind in many cultures at the time.

After these galleries comes a section on design propaganda, including war-related toys and clothing; then, the optimistic post-World War II era is represented. Showcased are eye-catching items that hip parents today would love to own, such as a sleek desk by Jean Prouve. This section of the show also reflects the era when the classic feel-good playthings came to market, such as LEGOs and Slinkys. Appropriately, the exhibition's historical and thematic flow then leads to a section that looks at how children have become consumers in their own right--and how designers began making goods created to appeal to little ones directly, not the adults that govern their worlds.

ENDLESS CREATIVITY, POSSIBILITY

"Design is always subject to influence by (and interpretation through) sociocultural norms, ambitions, and anxieties. Our exhibition focuses on the 20th century, but it seems clear to us that the boom in contemporary products for children is a result of the fact that -- because of the developments of the 20th century -- today pretty much anything is possible," O'Connor said, relating the ideas in the show to the current crowded marketplace for children's products.

"Developments in materials research, production techniques, and technology, paired with globalized communication systems and consumer markets, mean that designers and manufacturers have few creative limits in what can be produced for children," she added.

That can be both good and bad: I think of my own apartment, home to my two young sons and their countless figurines, miniature vehicles, building sets, art supplies, and books of every kind, both electronic and paper. Their and their peers' world is one of endless abundance in the 21st century, thanks to the progress of the 20th--but we, as many families do, I imagine, struggle with editing the sheer volume of playthings and educational objects that enter our lives.

Finally, the MoMA show concludes by addressing the optimism and social responsibility present in the design world today. It's a sensibility that was cultivated in the late 1960s and which has governed the lives of Generation Xers and Millenials since birth: the belief that design can help improve the world. Social innovation projects such as progressive playground design and the ubiquitous XO computer (from the One Laptop per Child initiative to bring computing to resource-challenged kids) are naturally on view.

"Although children's rights have come a long way over the course of the century, there are still design solutions needed. In fact, children continue to labor, and far too many are exploited and endure poverty and sickness," O'Connor said. "We hope that visitors will think about these issues and the potential of design to make further steps in the 21st century."

Some sub-sections seem slightly forced, such as a small display on hip Japanese art and design and its connection to cuteness. Others are so visually and thematically fascinating that they could easily be turned into their own exhibitions, such as a section looking at Space Age toys, and another quick one on playground design. If there is one criticism to be made about the show, is that it is so wonderfully thorough that it seems to be numerous shows in one. I wanted more--and began imagining potential exhibitions on toys and furniture for children in centuries earlier than the 20th, and then on various continents. And then it struck me as I was leaving MoMA: the core concept of "Century of the Child" is so much bigger than design for kids. The very concept of childhood, it seems, can be designed and re-designed itself.

All images courtesy the Museum of Modern Art. Child's wheelbarrow © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Beeldrecht, Amsterdam.

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com