Innovation

Dairy-based flame retardant could be a safer option

Could byproducts of cheese production replace fire resistant materials that are toxic to both our health and the environment?

Asbestos, when mixed with plaster, fabrics, and construction materials, makes them highly fire resistant. Breathed into our lungs, however, asbestos causes cancer. Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE), another common flame retardant, has been linked to thyroid problems in pregnant women and their children. A recent study on the phase-out of PBDEs in furniture foam, electronics, and plastics showed a positive impact: a 65 percent drop in the PBDE levels in pregnant women.

For a nontoxic alternative, a team led by Jenny Alongi from Politecnico di Torino in Italy mixed distilled water with powdered caseins -- which are found in whey, a byproduct of cheese production. Casein contains a lot of phosphate groups that quickly char when they catch fire, a dead end for a flame to follow, Popular Science explains. The char blocks heat transfer to unburned areas of the material, slowing the spread of fire.

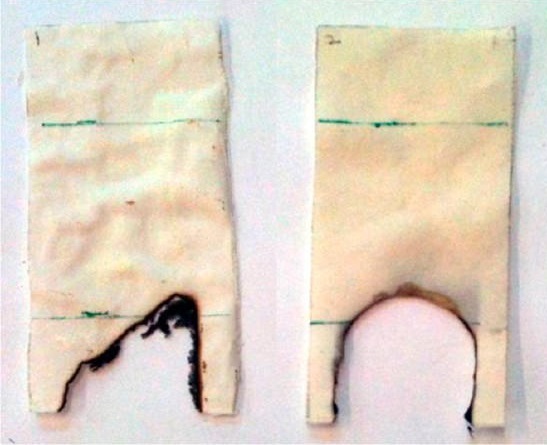

The team soaked cotton, polyester, and polyester–cotton blend fabrics in their liquid formula of powdered milk proteins, as Science News describes it. And when the fabrics dried, they laid them down on a flat surface and set them on fire. They found that the coating increased the fabrics’ thermal stability and flame retardancy.

- With casein-coated cotton, flames extinguished themselves in 75 seconds, after consuming only 14 percent of the fabric (pictured above, left).

- Only 23 percent of the casein-coated polyester burned before the fire ran out of fuel in 54 seconds (pictured above, right). The fabric coating decreased the polyester’s burning rate by 70 percent.

- The polyester-cotton blend (65 percent polyester, 35 percent cotton) burned completely, but the fabric burning rate slowed down by 40 percent, compared with an untreated blend.

The phosphate-rich caseins share similar properties with ammonium polyphosphate (APP), a common fire-proofing material that forms phosphoric acid under high temperatures. That acts as a molecular firewall, Science News explains, and keeps the flames from fanning out. But unlike APP, they don’t produce toxic fumes during combustion.

In countries that produce a lot of cheese, such as Italy and France, the proteins are cheap and abundant, Alongi tells Chemical & Engineering News. But the researchers will need to find a way to make sure the coating doesn’t wash out of fabrics, as well as a way to remove the molecules associated with casein that produces odor... materials treated with caseins smell rancid.

The work was published in American Chemical Society’s Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research (I&EC) last month.

Image: Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com