How technology drives up health costs

A new printer, no matter its cost, or the cost to use it, would be the coolest thing to have. If necessary you would tear out your whole network, all your PCs and other peripherals, just to support the latest printer.

Even if you had to pay thousands of dollars to print one page, you would justify it as necessary.

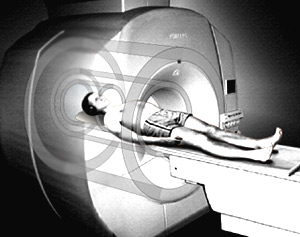

That's health IT. That's how the industry has evolved over the last decade, from CT scanners and advanced MRI machines inward, rather than from PCs and networks outward.

Moore's Law doesn't stand a chance when the state-of-the-art at the top end is all that counts.

There are good reasons for hospitals to have the latest imaging equipment. Today's gear gives patients much smaller doses of radiation than in the past. Radiation cost is why scanning had been limited. As that cost goes down demand goes up.

When a new MRI machine costs $1 million you have to charge thousands of dollars to use it. But lower radiation costs, and better resolutions, both drive doctors to demand more scans, which they can then excuse as defensive medicine -- fear of lawsuits. (Thus lawyers are looking at over-use of imaging as grounds for suit.)

Everyone winds up getting too many tests, and when doctors own the equipment the conflict of interest should be obvious. But it is largely unexplored.

Right now the pushback against this is political and scientific.

To be effective it has to become economic.

By that I mean we need incentives for doctors to benefit financially when they reduce their reliance on expensive tests, and a requirement that use of the pricey peripherals be justified before their use and audited afterward.

Data can help with that. Larger population studies, examining results from millions of patient profiles, can tell you the relative value of scans. These results get more granular as more data goes into the pile. If we have data on 1 million 55 year old men with hypertension, in other words, we have more validity than when we have data on 1 thousand.

Those results need to go into best practices that physicians are told to follow. Exceptions are possible, but they need to be noted, their results tracked, and doctors held to account when it's proven they are chasing too many wild geese.

The best price-performance in the hospital industry today comes from systems like Intermountain that also insure people and thus have an economic incentive to both limit scans and deliver results.

Aligning market incentives with efficiency, forcing doctors to justify use of the printer, is the thumb that needs to go on the health cost scale.